Anyone who has spent more than ten minutes in Austin has heard a reverent reference to the Armadillo World Headquarters. Though the club has been closed for over forty years, it maintains a mythical status as a symbol of a time when Austin was undeniably cool, and long before anyone felt the need to ask if it was still weird. It operated during an exciting time in Austin. Darryl K. Royal coached the Longhorns, rising political star Ann Richards was elected to the Travis County commissioner’s court, and Willie Nelson moved to town. Things were happening, and the Armadillo was at the center of it all.

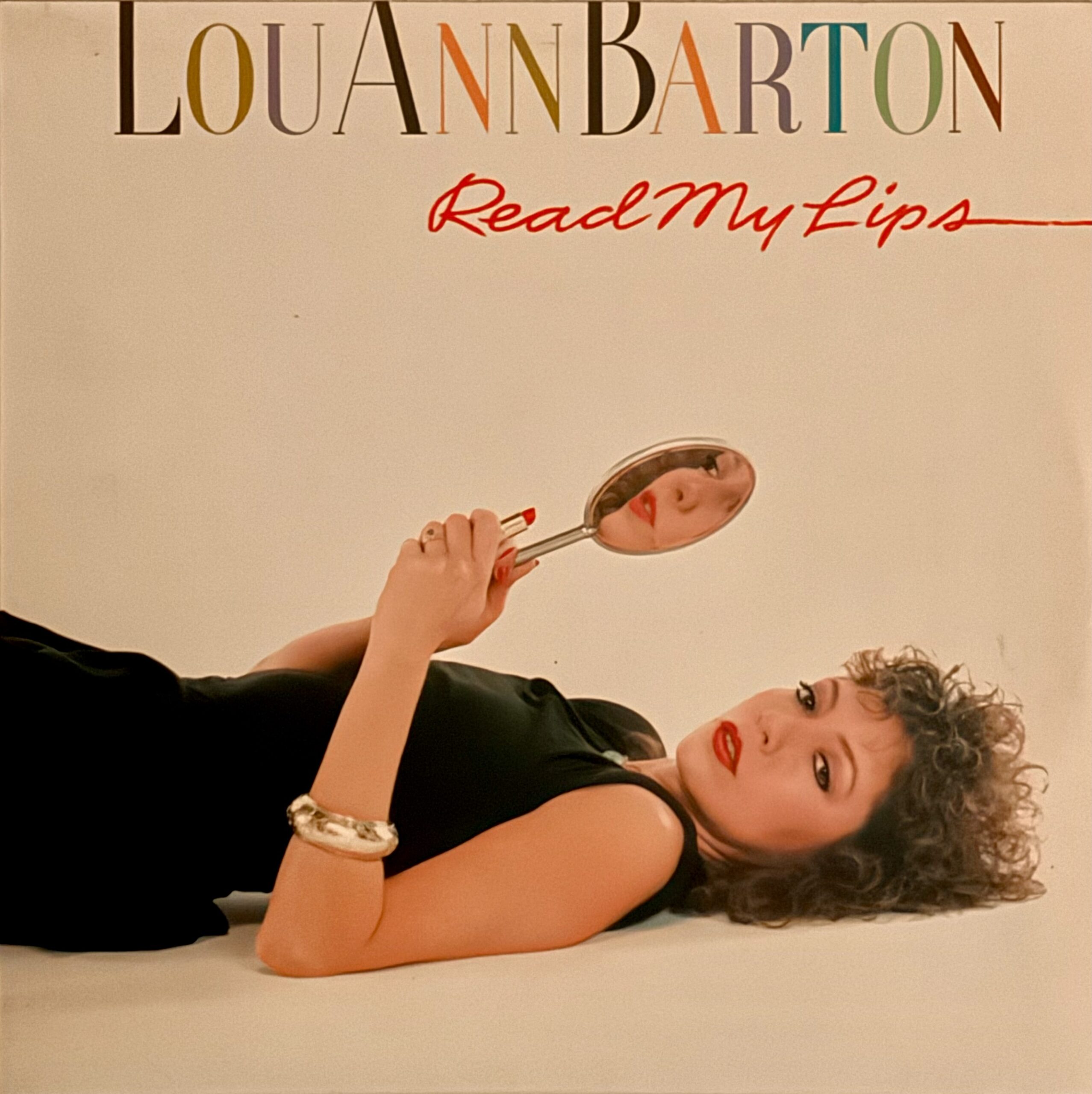

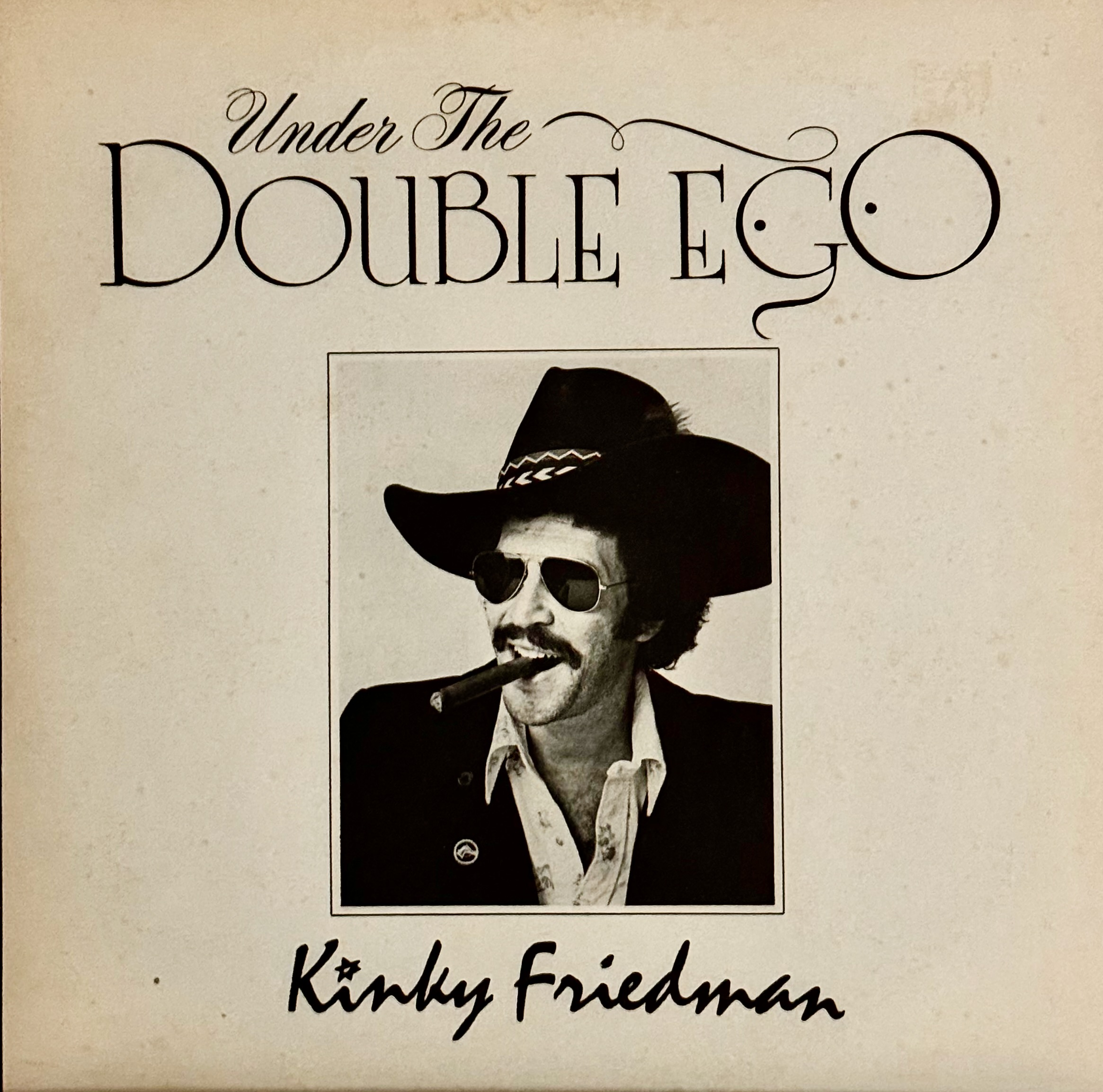

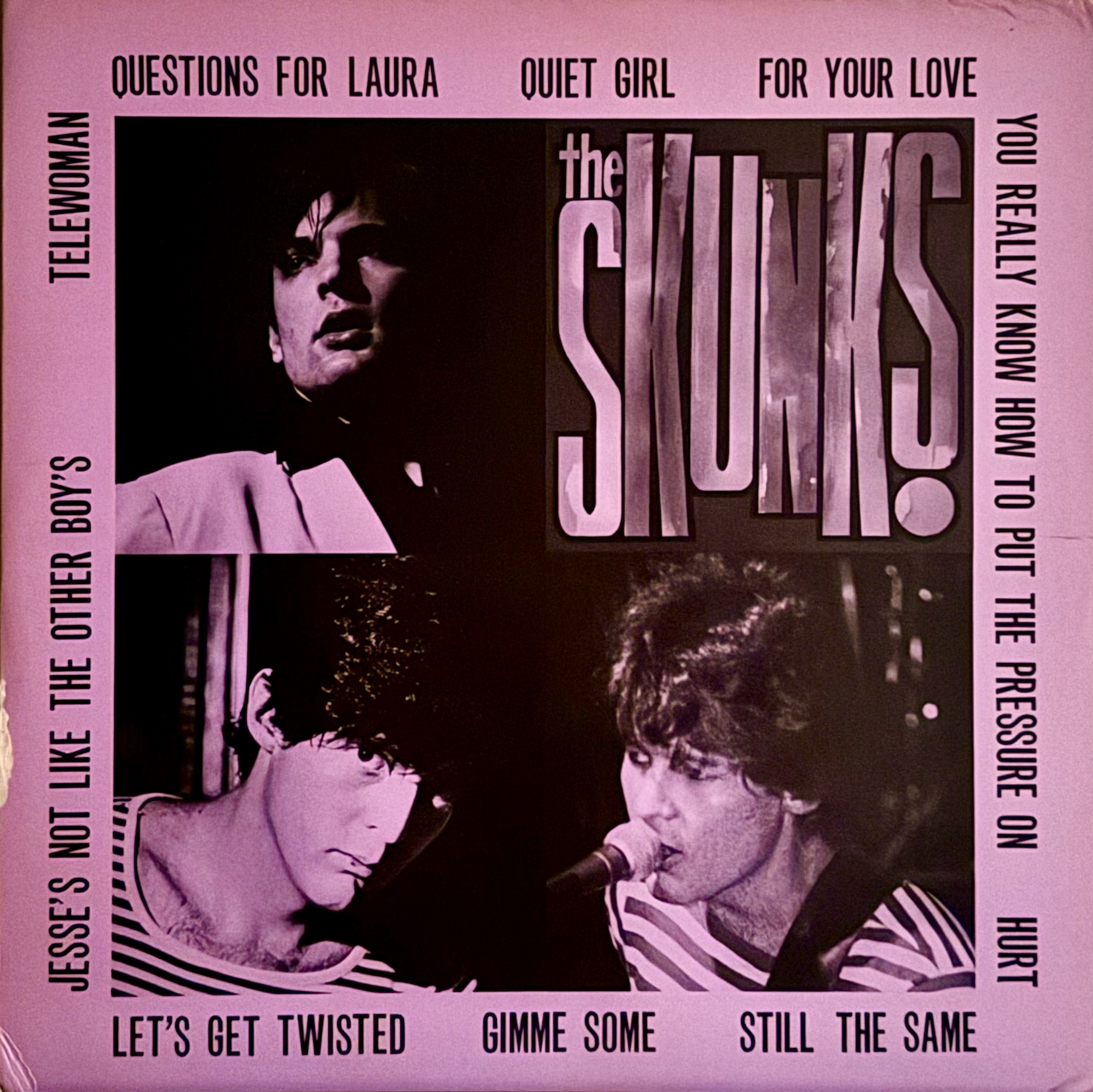

It was a cultural hub, anchored by a live music venue that operated for precisely one decade—the seventies. Conveniently, it was the same decade Willie Nelson, Asleep at the Wheel, and the rest of the cosmic cowboys claimed Austin as a musical alternative to Nashville. While the Dillo hosted acts from all genres of music, they’ve always been most closely associated with a fusion of rock and country. They hosted performances from artists including Bruce Springsteen, Frank Zappa, the Ramones, and Ray Charles, but history mostly remembers the music that brought the hippies and rednecks together.

The performance hall was an austere structure located on Barton Springs Road that had previously served as an armory for the National Guard. Founder Eddie Wilson discovered the building by accident one night while looking for a secluded area to empty his bladder. The space boasted a cavernous performance space, a built-in concrete stage on one end, and a bathroom designed for an army. It was functional, but it lacked creature comforts like air conditioning and needed a permanent smog of marijuana to mask the odors that clung to the building.

In addition to the performance hall, there was a beer garden serving pitchers of Lonestar and generous servings of cheap food. One of the claims to fame is the popularization of the nacho. The Tex-Mex classic was invented in the border town of Piedras Negras, roughly four hours south of Austin, and it worked its way up I-35, just in time for the Armadillo World Headquarters to become the first major venue to serve nachos, now a ubiquitous dish in stadiums and arenas across America. Whether it was cuisine, music, or art, the Dillo was ushering in a new era in popular culture.

They approached business with the nonconformist idea that things could be done differently, and could be done better by those willing to challenge convention. The building was home to more than just a music venue. The enterprise also included a bakery, a marketing team, an art studio, the aforementioned kitchen, a beer garden, and a variety of other businesses—all operating under the Armadillo umbrella. Even the Austin ballet company found a home here, a further testament to their openness to all expressions of art.

Jim Franklin and the Armadillo Art Squad played the largest role in ingraining the Dillo into the psyche of the city. Franklin made a name for himself drawing posters for the Vulcan Gas Company, where he incorporated the armadillo as a signature feature of his art. His work established the nine-banded creature as a mascot for the counterculture crowd hanging around Austin’s rock clubs, and it was a natural progression for it to be adopted as a namesake for Eddie Wilson’s new club. The concert posters created by the art squad are legendary among music enthusiasts and brought a broad appreciation to the genre.

The club was a DIY operation that nurtured a sense of community among the patrons. There was typically a collection of carpenters hanging around, and they were amenable to sharing a joint while brainstorming ideas like how to add a roof to a beer garden or air conditioning to an abandoned armory. Most challenges were confronted by a crew of employees supported by volunteers who were willing to work for free beer and grass. Not all of the ideas worked, but that didn’t discourage them from trying.

Cooling the expansive space of the former armory didn’t seem feasible until someone caught wind of a contraption the Houston Fire Department was using. They had a compressor attached to manholes to cool the labyrinth of tunnels under downtown. If the contraption could cool subterranean Houston, surely it could cool the Dillo, they thought. But after investigation, the team concluded that an armory and a sewer tunnel had irreconcilable differences. However, the more conventional awning they added to the beer garden did provide welcome shade during the hot summer months.

The club was a community, and they welcomed musicians into their midst. When a tour bus pulled in, Eddie Wilson made sure there was a crew to unload the equipment. The kitchen staff greeted the weary travelers with chocolate chip cookies. The philosophy was that a happy crew equated to a happy artist. While the crew took care of the heavy lifting, they would send the musicians to swim in nearby Barton Springs and then serve them a home-cooked meal before the show.

The kitchen wasn’t fancy, but they served Tex-Mex food to folks who were trying it for the first time. The nachos weren’t the only claim to fame. The shrimp enchiladas earned a particularly good reputation as well, with Jerry Garcia being a vocal proponent. After the Beach Boys tried them, they changed their contract to stipulate that any show within one hundred miles of Austin had to be catered by the Dillo kitchen crew.

The same DIY spirit that went into solving practical problems was embraced by the marketing team as well. One of their first challenges was promoting Willie Nelson’s first Fourth of July picnic. They only had a few weeks to co-produce the event, and there was a significant chance of failure. There had been a country music festival in the same location the year before, and the expected crowds never showed. Unlike the previous festival, Willie’s event didn’t feature big-name stars.

The Armadillo marketing team decided the trick was to use the entire budget to advertise the country festival on rock radio stations. They saw Leon Russell’s appearance as the key to promoting the event. Unfortunately, his contract didn’t allow them to advertise it, so instead, they whispered the secret into every DJ’s ear and made them promise not to tell anybody. They would also mention that Doug Sahm was performing, but they weren’t sure if he was bringing his friend Bob Dylan or not. The strategy worked, and around seventy thousand fans showed up to inaugurate the traditional concert.

The marketing team also played an essential role in establishing Lonestar’s regional dominance. With the Dillo selling more draft Lonestar than anywhere outside the Astrodome, it was natural for the brewery to ask for their help in waging a turf war against Coors. Soon, red, white, and blue Long Live Longnecks bumper stickers were adorning pickup trucks and VW buses across the state, and Jim Franklin’s art helped solidify Lonestar’s status as the national beer of Texas.

The Armadillo World Headquarters has been gone for decades, but its spirit continues to inspire the city. The Austin FC released a special edition Dillo jersey for the 2024 season in a valiant attempt to associate the new team with old legacies. Armadillo artwork still decorates the town, and when we call ourselves the live music capital of the world—we typically point to the bands that played at the Dillo forty years ago to prove our point. In the lore of Austin, the Armadillo World Headquarters is both a memory of what was and an ideal of what can be.